On Buoyant Form

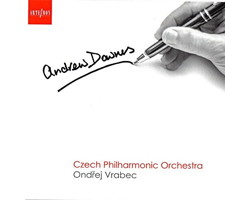

Orchestral music by

Andrew Downes -

heard by

RODERIC DUNNETT'... varied, innovative, involving and absorbing.'

|

|

Born in Handsworth, north west Birmingham in 1950, Andrew Downes studied composition at St John's College, Cambridge and later with Herbert Howells at the Royal College of Music.

Downes falls into a group of British composers whose talents are undoubted, but who have still to be allotted their properly appreciated place in the music of their native country, and to be fully recognised for their creative spark and individuality. His gifted contemporaries include notables such as John Casken, Judith Weir, David Matthews, Michael Berkeley, Philip Wilby, Robert Saxton, Simon Holt, Michael Finnissy, John Woolrich and Dominic Muldowney.

A few of that generation — Oliver Knussen for instance, or Colin Matthews and George Benjamin, have been treated as talents of the very front rank. But until the arrival of James MacMillan (born 1959), almost all these cogent figures are, well, insufficiently and only intermittently honoured, and on the whole less frequently performed in Britain or abroad. True, their new works are trumpeted and arouse some modest excitement; but regrettably revivals are few and far between.

This collection from 2015 puts Downes — at last, and deservedly — very much in the picture. As well as a double disc featuring four symphonies and two additional works, this box includes a DVD which contains a documentary film on Downes and on the making of these recordings.

Watch and listen — Andrew Downes — Music, Pleasure, Hope

(DVD title 1 chapter 1, 16:14-17:19) © 2015 ArteSmon:

Downes is a highly respected, original thinking composition teacher living still around Birmingham (having been head of composition at the Birmingham Conservatoire); but it is his own compositions that are given such potent readings here. The enterprising Czech ArteSmon label excels itself in serving up a clutch of gripping symphonic readings by the legendary Czech Philharmonic Orchestra under Ondřej Vrabec. They surely do him proud. His individual voice speaks loud and clear.

Downes reveals here a range in his output that is varied, innovative, involving and absorbing. In his Third Symphony, 'Spirits of the Earth', one of the four included here (and first heard at Birmingham Conservatoire), he is not afraid to derive, as he explains, 'exciting rhythms, counter-rhythms and musical influences from many cultures.'

Listen — Andrew Downes: Allegro ma non troppo (Symphony No 3)

(CD2 track 1, 0:00-1:16) © 2015 Artesmon :

African and Native American have their place, especially in both the Third and Fourth symphonies, as do jazz, big band and (in the Third) a marimba yielding the sound of a broad African savannah.

Listen — Andrew Downes: Molto vivace (Symphony No 3)

(CD2 track 3, 0:00-1:09) © 2015 Artesmon :

A reflective, folk-like theme on the flute, surely reminiscent of Debussy's Prélude à l'après-midi d'un Faune, characterises the opening of the Third's second movement.

Listen — Andrew Downes: Very slow, spatial ... (Symphony No 3)

(CD2 track 2, 0:00-1:15) © 2015 Artesmon :

A slow moving ostinato brings a wan feel to what follows. In the same symphony he talks later of evoking 'broad lines full of elation ... a feeling of old spirits coming alive and sounds which suggest creatures in the woods and jungles of the world.' These symphonies are certainly, as this might suggest, powerfully evocative, spirited, wide-ranging in cultural reference and full of atmosphere.

In his Fourth Symphony, crafted specifically for concert wind band, he ventures farther, and describes the vital and energetic gradual opening up of city life — Albuquerque, in New Mexico — and the rural hinterland, with much reference to the musical tradition of the Pueblo Indians; progressing to the desolation of the vast desert, the Chihuahua, characterised not just by modes and the solo cedarwood flute,

Listen — Andrew Downes: Andante e molto espressivo (Symphony No 4)

(CD2 track 8, 0:00-0:36) © 2015 Artesmon :

but 'funereal, processional-like music' — a recurring feature in many of Downes' movements — ', dissonance, large and jagged intervals.'

Listen — Andrew Downes: Andante e molto espressivo (Symphony No 4)

(CD2 track 8, 3:01-4:00) © 2015 Artesmon :

When the music at last flows relaxedly and beautifully, as it does during the last movement, it supplies a different, lighthearted mood for an evocation of a river: the spacious Rio Grande.

It is not least in his expressive combinations of instruments that Downes shows an unusual freshness and originality. For instance, the flute (and also the horn) features prominently in his works as a whole. A Sonata for 8 flutes emerged in 1996, heard at the USA National Flute Convention's Annual Convention in New York. This followed a Sonata for 8 horns; a year earlier, and later came a Sonata for 4 horns, a Suite for 6 horns and a Brass Sextet. His sonatas include one for contrabass flute and piano. Perhaps most off the beaten track is his Five Dramatic Pieces for 8 Wagner Tubas, written for the horns of the Czech Philharmonic, the orchestra that figures here on this disc. Here is a composer who has the gift of counterpointing not just a wide span of instruments, but drawing out contrasting sounds from groups of the same timbre so as to find a range of sounds and cavorting interplay from the same instruments.

This is, as mentioned, a double disc from ArteSmon, with an additional twenty minute DVD which explores the process of preparing and recording Downes' expressive, highly coloured symphonic work. Overall the collection has a lot to offer. There are the four symphonies (Nos 1 to 4), and two characterful, rather substantial concert overtures, both exemplifying those characteristics that lend Downes' output its distinctive and individual personality.

Numerous features, often lively characteristics, stand out in much of this music, some of which are almost like recurrent Leitmotifs to which he returns with dogged determination or passionate fervour. He draws on a considerable variety of patterning, of orchestration, of delicacy or insistency, ranging from a grim darkness, here and there echoing Holst's The Planets, mournful tolling and palpable sense of threat (notably in Symphony No 1: premiered in 1984 at the Cheltenham Festival), after he had written a dramatic cantata A Child is Singing, in which he has mentioned that a sense of acute foreboding regarding nuclear war played a role: indeed foreboding and severe anxiety describe Symphony No 1's pounding and awesome atmosphere very well.

Then, too, even in the same symphony or same movement, he exhibits a gift for evoking mystery and a forlorn loneliness, a kind of Lutosławskian contemplation, abetted by use of solo organ (which plays a substantial role in this work). This is offset elsewhere by a wide range of sparkling, toccata-like thrust and urgency, as in this example from the second movement:

Listen — Andrew Downes: Ricercare — Andantino con moto (Symphony No 1)

(CD1 track 2, 3:10-4:38) © 2015 Artesmon :

Frequently a feeling of serenity is underscored by a haunting use of chorale, often enough a brass chorale. Perhaps above all, in the music above, we encounter Downes' calculated use of a significant short theme or motto, a pattern not so very unlike BACH or DSCH, but very much one of his own, which he works and reworks and twists and turns like a Catherine Wheel as the work advances.

The opening movement of Symphony No 1 unveils this persuasive motif, initially brief and compact, but gradually expanding, and rehandled in several ingenious ways: later treated chordally by the organ, and by stages in delicate, then darker, then serene strings, with a brassy fanfare interposed. One is tempted to suggest that this kind of motto, with the meticulously worked transformations that ensue or accompany it, is a salient feature of Downes' symphonic thought. He makes his material work, thanks to the flexibility he so deftly brings to it.

Listen — Andrew Downes: Prelude and Fanfare — Andante (Symphony No 1)

(CD1 track 1, 0:09-1:42) © 2015 Artesmon :

The darkness, a somewhat sinister hue or even vengeful and assertive utterance which is so violent, bitter and acidic at the start of Symphony No 1, is strikingly and unexpectedly altered in the same initial movement to an almost pastoral demeanour: this becomes moody and grim, then explodes in full orchestra: we might reasonably suspect that this is the original material, expressively teased out and constantly revisited in varying forms: a protracted sequence engaging a beautiful tenderness makes an alluring contrast with the more strident sections; in a later passage the bass lines grumble, perhaps not sinisterly but rather, uneasily. Darkness seems again to threaten, but if the mood is still a bit morose, it is also more reassuring, and it fades away with the slightest hint of optimism.

The organ leads here, still exploring a version, it might appear, of the main motif. A dance seems to be emerging, though when it does it briefly turns bitter, proceeding, alternately, to delicate and elegant, then more violent episodes, trombones to the fore, latterly, pouring forth a clutch of dramatic, imitative passages that build into a rapid chase before subsiding. The slowly trudging version of the theme that launches the last movement, and the reflective organ passage that intervenes, seem not so much a threatening colloquy as some kind of accommodation or conciliation.

Here, and earlier too, there arises a strong, marked and slightly unnerving, or possibly reassuring, feeling of kinship with the Lutheran chorale Ein feste Burg. One might speculate that this, or something akin to it, has some bearing on the principal motif. A dramatic outburst, sustained by a violent thrumming, is clearly in descent from the opening material; the sad solo trumpet which flows from it is as moving as that (say) from the equally haunting Fourth Symphony of the Austro-Hungarian Franz Schmidt; but this is doubtless coincidence, albeit arguably a happy one.

The final fadeaway of Symphony No 1 is beautifully nuanced, and subtly conceived. Downes has a gift, both in mid movement and in closing bars for such hushed dilutions and attractive diminutions. Their feel is invariably alluring and often quite mesmerising.

In the three movement Symphony No 2, where some of the material feels like our opening motif of Symphony No 1 revisited in different form, there is a kind of gorgeous, intimate, easily flowing pastoralism — a descending pattern recalling Vaughan Williams — at the outset, set against expressive and again slightly forlorn solos (tympani with double bass, trumpet, solo upper strings, horn, and particularly affecting clarinet), and a mood that the composer classes as 'rhythmic and frenzied' — Vaughan Williams once again. There is much here in a short space: the 'dreamlike' and, conversely, the fiercely dramatic and hauntingly syncopated. One moody, insistent sequence might be straight from Stravinsky. The solos, as they arrive, maintain the pastoral mood. Downes is as ever fond of fanfares, differently used at different points (here distinctly medieval in feel), most especially perhaps in the middle movement of Symphony No 2. As with Symphony No 1, the die away is exquisite.

Listen — Andrew Downes: Lento molto (Symphony No 2)

(CD1 track 5, 0:00-1:43) © 2015 Artesmon :

The opening of the Vivace is scarcely light: rather it is frenetic and pretty fearsome: the composer calls it 'busy', perhaps an understatement. Yet out of this initial blast comes an exquisite string solo, alternating with cheeky light brass, maybe (yet again) related to the motto of Symphony No 1; then more fanfares almost impudently riding over. The string, possibly cello, solo heralds a positive flurry of dancy fanfaring; the lush, tender pattern rounds off.

The eight minute Largo is also prefaced by questing solos, here mixed brass, horn joined by trumpet, and as the composer aptly says, plaintive in character. A beautiful, expressive theme emerges in strings, with others joining in: peace and serenity rule. When full orchestra bursts in, it is passionate and insistent, urgently thrusting, with some sense of threat. What follows is mournful, doleful, perhaps somewhat Shostakovich-like, yet also gently reassuring, meditative and rural: peacefully reflective, in fact. The horn fanfares are set lower, ascending up to the trumpets, and after a kind of joyous, almost filmic brief outburst, gentle horns hover over soft strings, and woodwind takes over, yielding an enchanting farewell.

Listen — Andrew Downes: Largo (Symphony No 2)

(CD1 track 7, 0:10-2:02) © 2015 Artesmon :

In the Cotswolds, the first of two concert overtures heard here, contains material from the symphonies heard above, newly treated. The VW-like descending pattern reasserts itself, aptly pastoral, and tenderly ruminating in strings at the outset, while horn replies and woodwind join in one by one. The same pattern evolves in counterpointed strings, and then grows into full strings in a mêlée before a brassy fanfare briefly takes over. A solo horn, expressive but not melancholy, makes a contribution, and heralds a free-for-all not excluding piccolos and plenty of percussion. The descending pattern emerges exquisitely in woodwind, quite confidently, and here the strings take up and a horn reiterates fragments of the earlier material, before things draw to a close with one of Downes' touching fadeouts. As an evocation of countryside, but also in its own right, In the Cotswolds strikes one as both enticing and powerfully affecting.

Downes' conclusions to movements are often abrupt, unexpected and either dramatic or mysterious: thus while the last movement of Symphony No 1 and first movement of Symphony No 2 resolve peacefully on to a reassuring pianissimo, the concluding Largo of Symphony No 2, lent charm by that 'plaintive' brass passage, gains a cheerful buoyancy before disappearing as if by magic; and the concert overture mentioned above, In the Cotswolds, includes several of these features — a chorale feel, the use of a recurrent although reworked motto (so significant in Symphony No 1), and long unfolding patterns that patently suggest Vaughan Williams, first in reflective mood, then unbuttoned and joyous.

The at times savage darkness of the First Symphony (1984, Cheltenham Festival) and to some extent the climaxes of the Second (1985, Sutton Coldfield) are, to a degree, in contrast to the comparative cheer of the five movements of the Third Symphony, whose molto vivace is brought added joy by spare, spirited elements, a bell-like feel emerging from gentler, more optimistic woodwind, a rather wild buildup following an ostinato recalling Vaughan Williams, and (briefly) big, drumming brass that again cuts out almost impudently. This is pretty wild stuff, full of pertinent solos (trumpet, bassoon etc). Yet as so often with Downes, it can be interspersed not just by chorales, but by sudden gentle moments as if to make the forward thrust breathe before the onward helter skelter takes up again. The close is explosive, till it suddenly, almost cheekily, stops.

Indeed Symphony No 3 banishes all gloom at the outset: with inviting then gleeful percussion (especially marimba) and strings, Downes unfolds from this a dance bringing together, in a successful fusion, different popular idioms, lending it all the joy and syncopated vitality of, say, Copland, or indeed Bernstein: a quality that will reappear later in the molto vivace third movement. Percussion adds spirit, and different sections of the orchestra bring their own buoyant contributions. Twirling patterns are interspersed, as the energised syncopation grows more forceful and vital, before a more sustained, reflective sequence, as the vigour eases off, concludes with a patter or motif that we now see, or at least may speculate, has permeated and given life to the whole movement.

The relaxed, assured and enabling conducting of Ondřej Vrabec (who as a horn player himself has a splendid grasp of the composer's particular passions, one might even say foibles and teasing vivaciousness), gives this a cheeky and impudent lightness, though there is a sense of Downes' favoured chorales in the woodwind also. The ensuing movement of Symphony No 3 ('very slow, spatial, reflective') gradually emerges as song like, though it gains the flavour of a dance too, a sweet and charming one, lighthearted but there are other salient characteristics: a long, benign and enchanting flute solo that leads off the new passage, chased by a gentle rocking two note string ostinato.

A sense of mystery pervades the middle strings, and the rocking motif returns with a fuller accompaniment, confident and assertive, and cheerfully optimistic, before yielding to one of those characteristic diminuendi and attractive fade downs.

A feeling of urgency, related to the syncopated patterns above, launches the dashing Molto vivace. Brass takes off, but where we expect dazzle and frantic activity a characteristic chorale is opened up with woodwind cheerfully echoing the bossy brass. The domineering bit comes near the end, where violent thrumming and boldly proclamatory assertions lead to a quick ending. It exemplifies both that welcome variety with which Downes endows some, or most movements, and those particular qualities, almost like Leitmotifs, which are recurrent features of his style.

The fourth movement, entitled 'Belas Knap' after the famed Neolithic burial chamber atop the Cotswold Hills, brings a similar series of exchanges of pace and mood, attractively varied. The final Allegro molto is, not surprisingly, full of zest and drive, with both solo and collective brass. The percussion is emphatic but if anything more restrained also. A rising pattern emerges almost hymnically, and as elsewhere, Downes takes this sequence of notes and produces from it, first a sped up version, and then a genuinely hymnlike passage, an exotic solo string first echoing the slow section then tentatively beginning to dance, or at least gyrate, before the hymnic material returns and leads to a reassured conclusion.

Symphony No 4, as briefly indicated above, is inspired by New Mexico, by the characterful city of Albuquerque, the San Diaz Mountains (which suggest the cheerful second movement), the Chihuahuan Desert and the Rio Grande. Within seconds of its gentle start, one of those motifs we have met before bursts out, to be presented in various delicate and subtle reduced forms. This first movement, 'City', classed as 'Adagio', is largely serene, though that does not prevent the occasional outburst. (Symphony No 4 is scored without strings for Concert Wind Band.)

All dies away, opening the door for quasi military fanfares galore, somewhat cheerfully galumphing, to launch 'Mountains'. Soon it gives way to a jolly song like melody, only to be reinterrupted by a hint of the fanfare. In taking over, the woodwind offers up a gentle, calming melody alternated with flickers of brass till the fanfare grows into a massed affirmation before cutting off.

'Sky City', movement three, an evocation of an ancient mountain settlement in New Mexico, is given over to a wondrous, folk like 'cedarwood' solo flute passage — see the musical example above — one which evokes, the composer says, the music of Pueblo Indians, which reappears after comment by the woodwind, and indeed again after a more boisterous interruption. All forces join in a kind of oompah, with brass that momentarily recalls Janáček's Sinfonietta. The marimba has its moment, the flute has its further say, but soft tympanum provides the atmospheric conclusion.

A kind of funereal gloom launches the fourth movement, 'Desert', which evokes, says Downes, 'the emptiness, sadness and fear of the unknown'. This, partly evidenced by some thick, even alarming textures: sequences of gentle paired brass, or soft woodwind, yield to an urgent pattering and ponderous brass, switching suddenly, as so often, to a serene passage, exquisitely rounded off, as if to suggest some kind of accommodation with the wild.

The Rio Grande (movement 5), so far from being a wild onrushing, is a rather gentle, happy sequence, with even the brass subdued, as if it were a place of peace, hush and tranquillity. The expected explosion never occurs. In some ways, this movement is one of the most successful of all, concentrating on the gentle sensation of peaceable flowing, and capturing its mood to perfection.

The fourth movement, again with echoes of the same motto, is largely enraptured, and uplifting, a horn (if not trombone) solo emerging prominently, and the oboe alternating with strings on buoyant form.

Copyright © 22 May 2018

Roderic Dunnett,

Coventry UK

|