View from the Celli

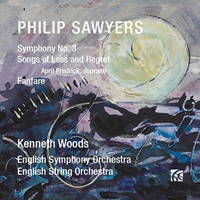

Philip Sawyers'

Symphony No 3 -

impresses

ALICE McVEIGH'Pummelled strings rise turbulent beneath great brass chords: the entire fisting orchestra soars, confident, triumphant and united at last.'

|

|

This is a fabulously tidal symphony, with wild expanses of differing moods, but it begins with a ripple of unease. We in the cello section were told to play the opening with as much stillness as possible, allowing the first theme to grow as it weaves into violins and violas, into threads of flute and oboe, and — from there — into a tempestuous section of interweaving themes. The argument descends into a woodwind quarrel, resolved by flute and oboe, decorated by horns — while the strings continue to niggle and churn away at any sense of calm.

Then solo bassoon ignites a new, still tenser, section. The violins take over, lightly but resolutely, answered by middle strings conveying a sense of tenderness — but with a bitter aftertaste. (This is incidentally one of Sawyers' most characteristic strengths: a tenderness, never saccharine, often undermined by subtle discontent.) From the brass comes the first glimpse of escape: the powerful broken octave theme over which the other themes furiously contend.

The cellos at the recapitulation, now deepened and enriched, are twisted by Sawyers into something passionate and grounded in lower brass, reinforced by timpani. The movement ends with the heavy brass seemingly triumphant over the strings' stubborn reiteration of the theme. Still, the lower strings' pessimism prevails.

Tutti violins kick-start the second movement with a dramatic leap from their richest register, only yielding to keening solo oboe.

Listen — Philip Sawyers: Adagio (Symphony No 3)

(track 2, 0:00-1:03) © 2017 Cedille Records :

The sobered strings leave the solo winds to mourn, yet, with characteristic Sawyers intensity, something is brewing at subterranean depths: eventually, the violas' chuntering is answered by full insistent brass, in a stormily ecstatic tantrum. Above rippling middle strings, uncertainty in the winds and answering horns unnerve us again. The electricity descends into glowering lower strings, uncertain winds are whipped towards the horizon.

The opening is then recalled, but with a bleak hollowness at its centre, horns — full of bravado — going unanswered, before descending strings and lower horns unite in an exquisite section as intimate as anything in late Elgar, the intense first theme finally quietened instead of questing, capable not only of compassion but — despite lingering doubts — perhaps even of forgiveness. Solo winds frame an aural halo over softening waves at the close.

I've had Sawyers' third movement here in my head for months, so I must insist upon here submitting my official complaint — except that — well, how can I? This delicate little throw-back is basically a stroke of genius. From the opening, very droll, bassoon, not to mention the quirky violins undercut by elegant sloping winds, Sawyers is leaning back and taking a cigarette break. (Kenneth Woods is lighting it for him. They are both attired in late Victorian dress.)

Light little runs toy with expectations, the rhythmic emphasis is played with, disputed (two, three? Who's counting?) The turbulent sea has disappeared. Instead, languorous, we are punting down a river in flickering summer sunshine, light trickling through the trees, to the sounds of distant cricket applause and dipping oars, birds soaring above. A few, faux-angry, interruptions cannot disturb anything so poised, sunlit and perfect. A mini-masterpiece.

But ... it is only an interlude, and the opening of the finale is already combatively arresting, with discontent surging acidic in twelve-tone strings amidst intermittent blasts of impatience from percussion and brass.

A rich chorale eventually emerges, (described by Sawyers thus: 'I like the idea of an emerging harmony from contrary motion — the notion of a harmonic 'still' or 'focussed' point moving to more dissonant chords.') This chorale is undermined by high violins and objecting winds across a dystopian seascape. There are occasional whirlpools of orchestral colour — foreshortened attempts at fugal control — but every attempt at resolution is thwarted, sometimes by whipped imitation breaking out like white caps. Eventually the heavy brass overwhelms the strings' skittishness, a granite-coloured wave rises to crashing peroration.

But, as so often with Sawyers, something unexpected is conjured up. Solo winds softly recollect, brass interventions ebb into clouds of near-Sibelian levels of intensity. A yearning trumpet cries, solos strings aspire, against a background of flutes and slippery violin runs. Eventually the angular theme returns, but this time focussed, fugal. Sawyers screws his harmonic tension to tsunami point: implacable violins finally challenge the brass to one last long drawn-out chorale. Pummelled strings rise turbulent beneath great brass chords: the entire fisting orchestra soars, confident, triumphant and united at last.

Sawyers' Songs of Loss and Regret are very different from his latest symphonic glory. Their emotional scale is every bit as powerful, but being set only for voice and strings — Woods' notion — gives them still greater intimacy. Their order has an intuitive sense of pacing that I love, and the oftener one listens to them the more tiny, jewel-like subtleties one discovers. Any one of them would be a divine choice — for the right performer, of course — for an international lieder competition.

Listen — Philip Sawyers: From the Wisdom of Solomon (Songs of Loss and Regret)

(track 11, 0:00-1:18) © 2017 Cedille Records :

And April Fredrick was a superb choice as performer here. Her glorious variety of tone colours and effortless phrase shaping is ideally suited to this music, while her voice possesses a peculiarly lovely if risk-taking combination of clarity, strength and sorrow.

And she is such an intelligent singer! For example, in 'A Shropshire Lad' there is just a touch of poison on the word 'content' in the phrase 'the land of lost content'.

Listen — Philip Sawyers: A Shropshire Lad (Songs of Loss and Regret)

(track 5, 1:13-2:00) © 2017 Cedille Records :

And, in the second Housman selection, there is a flash of fury on 'a soldier cheap to the King but dear to me.' The third song is gloriously set: the high stranded violins at the conclusion especially moving, the final line 'And we were young' flung down by Fredrick like a gauntlet, the pacing death of the lowering strings, the pure raw harmony of the close.

In the livelier Tennyson the soprano sharpens, until the penultimate line, delivered with all of Fredrick's trademark pin-point wistfulness — 'The tender grace of a day that is dead/will never come back to me' ...

All these are admirable, however — for my money — the most terrifyingly beautiful — 'Futility' by Wilfred Owen — is one of the most glorious song-settings I've ever heard by anybody. Cellos and violas weave undulating lines restless under the voice, the deliberate disconnect between the purely lovely lines and the text feels almost unbearable. The singer's indignation flowers: 'Are limbs — full nerved — still warm — so hard to stir?' and subsides in anguish in 'At all, at all.' Fredrick's lingering chilled delay in vibrato on the last 'all' is, quite simply, inspired.

Gray's 'Elegy' sets forth with new power and impetus, with martial rhythms and a sardonic undertow, until the last acid line 'the dull cold ear of Death.'

The song from the Apocrypha features a lovely violin line on 'and our spirit shall vanish as the soft air'. Fredrick's wild (but never shrill) cry on 'remembrance for our time is a very shadow that passeth away' lingers in the ear, while the double bass ending into the depths is superbly paced, by Woods.

The second loveliest song for me is William Morris' 'Song from the The Earthly Paradise'. The resigned yet glowing melisma on 'love' in the line 'If fear beneath the earth were laid, if hope failed not, nor love decayed' ... the bloom on Fredrick's unforced silver-gold voice ... a voice endlessly fascinated by its own possibilities. Woods excels: he never inserts himself above the music, and his handling of each of these short glories is sublime: the balance — not only within the orchestra, or between voice and orchestra, but between so many, often fleeting, emotions — is exemplary.

Sawyers' Fanfare, is, as you'd expect from Sawyers, not your boring average fanfare: its traditionally celebratory section is subtly undermined by darker notes. But you should not buy this CD because of the fanfare. You should buy it for his tidal new symphony — and for the tiny jewel-like flames of his song cycle. These are why.

Copyright © 5 December 2017

Alice McVeigh,

Kent UK

|