|

Museum Culture?

Experimental music by Cage, Cowell,

Feldman, Rzewski, Satie and Wolff,

heard by MALCOLM MILLER

If anyone had the impression that the experimental schools stemming from the 1960s had run their course, they would have been happily surprised by the recent three-day festival Experiment!, presented by the London Sinfonietta at Kings Place, London, UK (29 April to 1 May 2010). For alongside highlights of the American and British schools of the sixties and seventies, the programmes featured a European première of a new piano work performed by the composer Frederic Rzewski, fresh spontaneous improvisational music by a Scratch Band (structured on the lines of the original Cardew Scratch Orchestra) and a cutting edge crossover collaboration between the London Sinfonietta and (ever open to new influences ...) the pop-indie band 'Micachu'.

The concerts were spiced by foyer music, 'Meet the Sinfonietta' pre-concert interviews and the iconic Vexations by Satie, the 840 repetitions of its chord sequence played by a team of pianists between 6am and midnight on 1 May. The attractive format was devised by the new music author and broadcaster Robert Worby, designated 'curator', and indeed some of the older works performed have acquired the aura of a museum piece, yet no less relevant and stimulating for that. What emerged was the admirable extent to which a foremost new music ensemble such as the London Sinfonietta has addressed issues of accessibility and communication in new music to engage wider audiences, especially developing their recent residency at the sparkling Kings Place complex.

The first concert devoted to American Experiments (Thursday 29 April) was a memorable evening, including the European première of Nano Sonatas Book 7 played by its composer Frederick Rzewski, who also came on stage at the end to receive applause for the stunning performance of his 1971 'political' process piece Coming Together. The programme also featured works by Henry Cowell, an early pioneer of the experimental movement, and masters of the sixties, Christian Wolff, Morton Feldman and John Cage. The whole concert offered an inspiring experience of an important branch of the avant garde, akin to wandering around a modern art gallery of 1960s American abstract expressionism, exploring radical ways of apprehending the world. Hall One in Kings Place, though only two-thirds filled (what's new in new music?), formed an ideal venue for such a concert: its geometric patterns and natural wood finish both around the walls and in the high ceiling allow the mind to expand and meditate while the fresh new sounds resonate around the spacious, rhythmic building.

The first work set the tone, a beautifully meditative piece from 1923 by Henry Cowell, entitled Aeolian Harp, in which the player plucks the strings within the piano while holding down certain notes which allow selected pitches to resonate like the wind blown instrument of the title. John Constable's interpretation was serenely poetic, as he plucked delicately inside the piano, the harmonic progression unfolding its jazzy neo-baroque sequence, each chord prefixed by a magical glissando and each progression interspersed by an E flat arpeggio rising, pizzicato, from the bass. The resonant pauses enhanced the purifying aura, consonant yet contemporary.

A similar exploration of sound at the edge of silence, though here immersed in atonal harmony, was the 1975 piece Four Instruments by Morton Feldman, performed with nuanced subtlety by Laurent Quenelle, violin, Oliver Coates, cello, David Hockings, chimes and John Constable, piano. Indeed the Feldman was amongst the most arresting works of the evening, drawing our listening attention to the slow sustained resonances of the varying spatial groupings of timbres, with some unexpected attack points by piano, chimes, cello or violin. From just a few wisps of sound, with everything below pp, there was a paradoxical sense of vastness and stretched time, as one's ear was attuned to the slightest details of sound and gesture, silences and space.

The European première of Rzewski's Nano Sonatas, Book 7 (2010) was prefaced by the composer's dedication of the work to Annette Moreau, author and producer, who was present, for her contribution to new music in the UK. The pieces were composed and premièred in the USA only a few months earlier, yet this performance projected so much energy and focused intensity that every moment came alive as if for the first time. The seven sonatas, each about three minutes long, work wonderfully as a set, contrasting in mood yet paced into a broader unity. At the heart of each miniature is the sonata idea, a process of thesis, antithesis and dénoument. Each is an essay in 'chromatic scales', as the composer put it during an informal interval conversation, a type of study with a playful improvisatory element reminiscent of Kurtag's piano works.

The first sonata moved from leaping short gestures to smoother consonant intervals at its midpoint, returning to its initial terse pointillism at the end. The second evolved chromatic clusters and trills, the third resumed more brittle chordal gestures, expanded and intensified to a central climax and return. The fourth piece began with a rich minor mode saturation of clusters, gestures layered one upon the next, leading to a climax; while in the fifth, a high cascade of chromatic scales poured out one from the other; the splash of colour fading to a tiny ppp and then emerging into an almost violent fortissimo in the turbulent and soupy bass register. The sixth piece developed dyads, including consonant fifths, while the seventh and last began as a buzzing bee trilling, its rising themes and fast leaping chords turning at its centre to single pitches, widely spaced and punctuating the canvas, before resuming the earlier texture.

Acoustically rich due to the generous pedalling in all the sonatas, one was aware all the time of the remarkable range of pianistic colours emanating from Rzewski's fingers, displaying an ear for piano sonority rather than merely dry abstract patterns. Rzewski observed how he was striving to extend the range of dynamics and colour of the instrument which, from its inception, as the cembalo pian e'forte, was devoted to such contrasts. Rzewski himself often performs mainstream classical repertoire (he mentioned Mendelssohn as an example of a recent concert) and indeed in some of the sonatas, one could trace influences from the 'tradition' abstracted onto a highly abstract canvas, for instance the opening of the third in particular reminded one of the extreme rhetoric of late Beethoven, in its exploration of high and low registers and febrile texture.

In the second half of the programme, John Cage's Five (1988), a flexibly improvised work for five players, came across as a calm sequence of quiet harmonies produced by the apparently random sequence of instruments: it seemed more interesting as a concept, and indeed one could appreciate here the players' own musical choices of form and pitch. Far more involving was the graphically notated For Five or Ten People by Christian Wolff which followed, in which contrasts and unusual effects contributed to the dramatic interest.

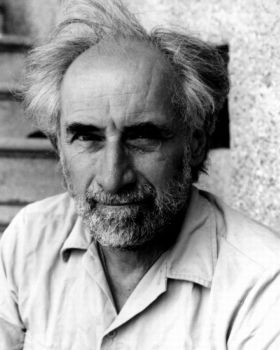

Frederic Rzewski

|

In some ways it was the final piece, Rzewski's Coming Together (1971), which best summed up the strengths of the experimental movement in its heyday: a formidable energy, excitement and spontaneity linked to potent political impact. The work sets to a 'sprechgesang' recitation a letter by Samuel Melville, one of the leaders of the Attica Prison Uprising in 1971, a landmark event in the context of race politics in the USA. Clearly influenced by works like Reich's 1965 It's gonna rain, looping sampled texts to generate tension and patterns, here the narrated repetitions, grippingly projected by actor Aled Pedrick, gradually built up emotional intensity, whilst also highlighting one line as a refrain, 'I think the combination of age and the greater coming together is responsible for the speed of the passing time'.

There was a mesmeric effect to the combination of subtly changing rhythmic melodic patterns in the ensemble, a type of 'riff and variations' form, with the seamless sequence of narrated statements, repeating and extending, and yet, like an Escher drawing, never quite arriving, until the very end. Here all the instruments join in a formidable unison illustrating the title's 'coming together', a climax which demonstrated the shift from the initial calm philosophy of the letter to an almost violent activism. It was a piece which clearly had relevance to the British experimentalists, for there exists a rare recording with Cornelius Cardew as narrator.

The excellent performance was alert to the marriage of minimalism and music theatre, creating an immediacy which makes the piece communicate with topicality even forty years after its composition. Such works raise intriguing questions as to the place of the avant garde in the 21st century, and whether experimentalism by its nature runs the risk of forming its own museum culture from which it is essentially striving to escape.

Copyright © 5 May 2010

Malcolm Miller,

London UK

|